| |

The drawing of Mountains

Nicolas Boldych

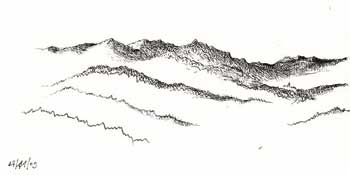

For a long time I have tried to draw mountains, without ever being satisfied with the results. For a long time I have tried to draw mountains, without ever being satisfied with the results.

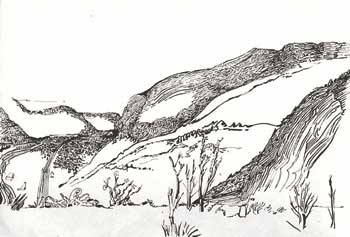

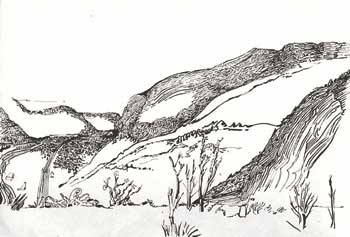

They are in front of you, massive and evident, at the same time shadow and light, axis and facade; and the drawing of their crests which flirt with the weightlessness of the clouds is clearness itself, an over-clearness one might say. And yet the shape of a mountain, and more still its volume, with its spirals, bends and folds, are seized with difficulty. The rock in a more general manner does not guide the artist's line: on a cliff, a rock, or even the slightest of stones, there are one thousand possible routes among which the drawing hand will have difficulty in choosing. When we draw living trees or animals, we draw a current process, the leaf wants to fall, the trunk takes hold of the ground, and the cloud itself has a purpose which it fulfils impassively.

With rocks, and the mountains, we find ourselves in the past, the archives, and the souvenirs. We graze, glance over the dry beings, without sap, old fossils millions of years old; and we hesitate and get lost among a labyrinth of tracks. In the face of the unprecedented complexity of the past when so many things were, and still remain, upon the mode of accumulation, one must be at the same time in improvisation and meditation.

The more these mountains were familiar to me, the more difficult it was for me to draw it. I knew them as faces, fronts, barriers, cliffs crossed by signs, dented or split skulls, shoulders grazed or covered with fir trees, fantastic beasts, giants.  Between each was a powerful border, a law which at once pressed heavily on nature, and transformed it into a heroic landscape, and glorified it. Between each was a powerful border, a law which at once pressed heavily on nature, and transformed it into a heroic landscape, and glorified it.

So many mountains, so many laws, so many names: Céüze, Sirac, Grand Ferrand, Obiou, Chaillol, each one alive, real, evident for me, but also for the men and women who live in Champsaur, Valgaudemar, Dévoluy. But how to convey these mountains? Through those signs which make them recognizable, readable and above all, that it has a direction for the "foreign". How to draw Chaillol, this axial, round mountain in its base, massive and solitary, solar also, and around which wind Tourond, Petarel, Chaperon. And Céüze? How to convey this mountain which is a little bit the Saint Victoire du Gapençais, a large forehead at the top of a slope which resembles a long nape running from the North to the South. Céüze, exiting Dévoluy, looks towards Durance, and beyond towards Provence. Céüze due to such a perfect shape, both face and profile, had to be a God for the Voconces tribes which populated the region, before the arrival of the Roman cartographers. But how to convey Céüze?

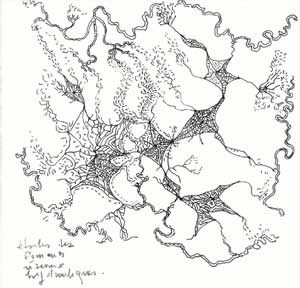

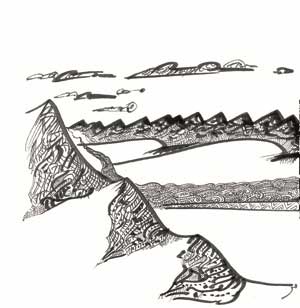

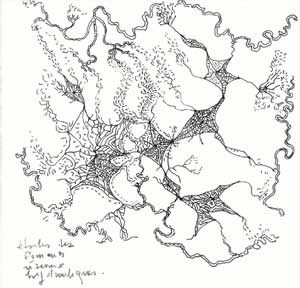

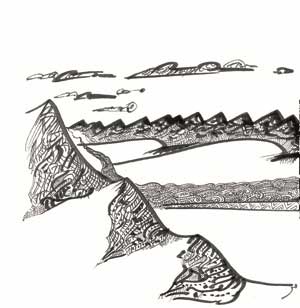

Fortunately, or unfortunately, the mountains are full of folds, wrinkles which roam, wave, wind over themselves and very often disappear, cut by a colossal force, broken in its tracks by another mass which ended up imposing its law. One can then try to follow its creases, out of loyalty, or out of love for the complexity and the whims of time. Instead of drawing the mountain as a  block, one seizes it, captures it then in a beam of features, veins and venules which may remind one of a cut-away diagram. It is a thrilling mountain which one draws then, a crystalline, glass mountain. block, one seizes it, captures it then in a beam of features, veins and venules which may remind one of a cut-away diagram. It is a thrilling mountain which one draws then, a crystalline, glass mountain.

It is what I made by trying to return the massif of the Chartreuse. That is I took refuge with the complexity, the sharpness, the detail; as if I had wanted to return the route, the steppings, the stars, hatchings, appropriate for a hand's lines.

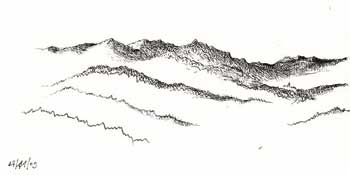

But mountains do not flutter like a hand; they are not as fragile as crystal. They have definitely matured, which makes them insensible to any shock. They dance like blocks. They are blocks which dance.

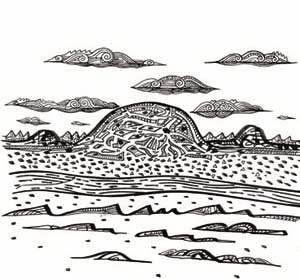

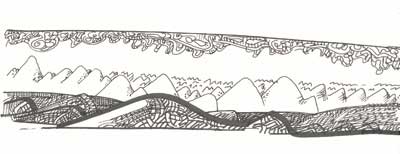

I also drew laces, laces of mountains, which could also be cardiograms, an accumulation of cardiograms which by crossing over itself would eventually draw the general shape of the mountain. It gives an impression of movement, trembling; it is the mountain-saw, the sierra.

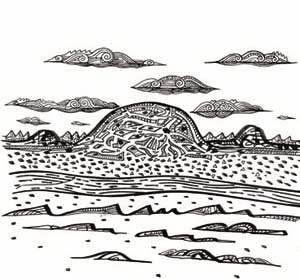

But the mountain does not come down to the nervous dynamism of a cardiogram; its rhythm is more general, deeper. No, the mountain is neither a crystal, nor a cut-away diagram, nor an opened hand; it is not only, at its summit, the clearness of a saw tooth line or, at its foundation, an accumulation of signs compressed by a primitive matrix: it is a block which dances. The mountain would have two aspects: an Apollonian aspect consistent in the clarity of summits and the crystal of figures, and a Dionysian aspect which becomes confused with the deep, intoxicating, primitive dance, which was that of the earth millions of years ago, in which the memory and continuance remain. Even frozen, stopped, they continue moving, dancing, the mountains dance, at least the Alps dance, and the Caucasus, Elbourz, Hindu Kush without a doubt also, although in reality I did not see them dancing. The monumental Ecrins dance; the beautiful spirals of the massive Belledonne, Oisans or Trièves also dance, in Isère. Maybe even by dancing they imprint a general rhythm in the terrestrial surface, which without them would be an apathetic lowland. mountain would have two aspects: an Apollonian aspect consistent in the clarity of summits and the crystal of figures, and a Dionysian aspect which becomes confused with the deep, intoxicating, primitive dance, which was that of the earth millions of years ago, in which the memory and continuance remain. Even frozen, stopped, they continue moving, dancing, the mountains dance, at least the Alps dance, and the Caucasus, Elbourz, Hindu Kush without a doubt also, although in reality I did not see them dancing. The monumental Ecrins dance; the beautiful spirals of the massive Belledonne, Oisans or Trièves also dance, in Isère. Maybe even by dancing they imprint a general rhythm in the terrestrial surface, which without them would be an apathetic lowland.

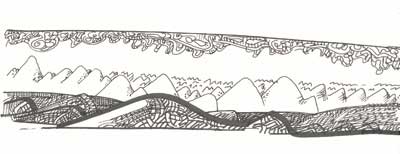

I then began drawing rhythms, spaces which are also letters, I decoratively wrote mountains, with uppercase letters – thick traits which render the general silhouette of mountains and hillocks, and lower cases, finer signs which represent its crystal, its faces. Uppercase letters are broad waves which give a group rhythm, while the fine signs are repeated, according to processes of acceleration or deceleration; these are stretched or released, tight or loose signs, inside a frame, a rhythm, a major dance. The mountains are like dancing handwriting; reciprocally the direction of a sentence curls, has summits, is momentarily a gentle wind,  waiting, before taking back its course. So, because of its physical and calligraphic aspect, the writing in itself becomes poetry. waiting, before taking back its course. So, because of its physical and calligraphic aspect, the writing in itself becomes poetry.

But besides dance, what could be the relationship between mountains and writing?

I would say that it is the fact that it tells and hides at the same time. The world which is on paper, the world of letters, writings, is only the shadow of the real world, it is the world of ink that in its sometimes perfect sequence, its network of letters, its pattern, would make one almost forget the real world; the universe enters the book's tabernacle. Also mountains talk and hide at once. The French Alps hide Turin, Piedmont, Italy, the Pyrenees hide and say Spain at once; these ancient, solid, imposing mountains, speak about the robustness and antiquity of Iberia.

So we end up loving a mountain for what it hides: a country, a culture, a civilization, a hereafter especially, which in spite of all the modern means of communication still remains mysterious "Die Bergen verbergen", "the mountains hide", one might risk this play of words in German. Switzerland surrounded by mountains is an almost occult territory, secret, safe and a water tower. What would be the Swiss myth without the mountains? The world stops at the foot of a mountain, and another one begins on the other side.

Let us take Grenoble then, this city surrounded by mountains which, if they act as nice pedestals at sunsets, they also hide it from the rest of the world, so it sometimes seems that this city is separate. In Grenoble we read the rest of the world in the writing of the mountains, in their phrasing, the dance of three ranges which are three links named Chartreuse, Belledonne, Vercors.

The Chartreuse is the holy mountain, the Sinai that one climbs like a staircase, a ladder, towards the Bastille and beyond, where a desert is hidden from the extraordinary greenery. It is also a stony casting which comes back into the city, strikes it, stops it. It is the hard law of the North, the Savoy, of Burgundy or Switzerland. The Belledonne range in the East is, on the contrary, feminine, jagged, carnal, and pagan, it says and hides Italy. To the west is Vercors, the poor mountain glides in parallel to the flow of the Rhone, but opposite this flow. The Vercors goes back up towards the north. The plateau of Vercors hides the Rhone and goes the wrong way from this river where it takes form and increases the power of the South. The Vercors says and hides the South. jagged, carnal, and pagan, it says and hides Italy. To the west is Vercors, the poor mountain glides in parallel to the flow of the Rhone, but opposite this flow. The Vercors goes back up towards the north. The plateau of Vercors hides the Rhone and goes the wrong way from this river where it takes form and increases the power of the South. The Vercors says and hides the South.

Every mountain has its writing, its dance. A heavy, massive dance, of the Pyrenees, dizzy dances of the Alps or Himalayas, asymptotic movements of the Dolomites which are mountains-pillars advancing in a group towards Venice, every range of mountains develops a unique style, in the crossroad of several countries or cultures, such as the Balkans, these controversial mountains, and always in war: the Greek "Vouno" against the "evil" Albanian, the Bulgarian "Planina" against the Serbian "Gora"…

From the mountains surrounding Grenoble, I thus began writing these mountains which in my mind form an uninterrupted range, an endless range which by provoking, by separating or by protecting cultures, civilizations, ends up a little by forming the spinal column of the world, its dance. What would the earth be without mountains; would there be a world without them, a direction in the world, landmark points, a physical, religious geography? They would not have these visible signs all over.

At the beginning there was the violent dance of the blocks which as a result become the signs given with regard to everything. In the South some are sierras - consequently in Spain or Latin America - for others they are djebel in Maghreb, the forms, like the words which say the mountain, change: mons, oros, montagna, munte, mal, gora, each of these words corresponds without a doubt to a cultural, mythological, religious historic vision of what the mountain is; dag inTurkey, Shan in China, Yama in Japan. Each sound must speak in its manner of an origin. Gunung Indonesia, menez Breton, vouno Greece. These are words, sounds, probably untranslatable and with very particular meanings, because even physically the Norwegian mountain enters the sea, it is  not the Tibetan axial mountain, which is not itself the mountain-volcano of the Indonesian archipelago, or because the Apennines act as the spinal column in a country, while the Caucase separates the world from the steppes of the Middle East. Their action, their function is not the same. And their name also, consequently. From country to country, from continent to continent, mountains do not make the same thing. Until the north. not the Tibetan axial mountain, which is not itself the mountain-volcano of the Indonesian archipelago, or because the Apennines act as the spinal column in a country, while the Caucase separates the world from the steppes of the Middle East. Their action, their function is not the same. And their name also, consequently. From country to country, from continent to continent, mountains do not make the same thing. Until the north.

In the north, even if there is not much to hide which is rare with humans, the mountains still exist: fjall Norwegian, Icelandic, and even Danish, mägi Estonian, vuori from Finland… After the mountains of Greece or America, I continued writing decoratively and also crossed over them, trying to imagine their arctic dance which finishes and begins in the Sea and gets closer to the pole.

Chile, New Zealand, Africa, Altaï, Others will come, still and maybe they will end up forming a large book which could be called, without searching very far, "The mountains of the world". Nicolas Boldych illustrations

|

|

For a long time I have tried to draw mountains, without ever being satisfied with the results.

For a long time I have tried to draw mountains, without ever being satisfied with the results. Between each was a powerful border, a law which at once pressed heavily on nature, and transformed it into a heroic landscape, and glorified it.

Between each was a powerful border, a law which at once pressed heavily on nature, and transformed it into a heroic landscape, and glorified it. block, one seizes it, captures it then in a beam of features, veins and venules which may remind one of a cut-away diagram. It is a thrilling mountain which one draws then, a crystalline, glass mountain.

block, one seizes it, captures it then in a beam of features, veins and venules which may remind one of a cut-away diagram. It is a thrilling mountain which one draws then, a crystalline, glass mountain. mountain would have two aspects: an Apollonian aspect consistent in the clarity of summits and the crystal of figures, and a Dionysian aspect which becomes confused with the deep, intoxicating, primitive dance, which was that of the earth millions of years ago, in which the memory and continuance remain. Even frozen, stopped, they continue moving, dancing, the mountains dance, at least the Alps dance, and the Caucasus, Elbourz, Hindu Kush without a doubt also, although in reality I did not see them dancing. The monumental Ecrins dance; the beautiful spirals of the massive Belledonne, Oisans or Trièves also dance, in Isère. Maybe even by dancing they imprint a general rhythm in the terrestrial surface, which without them would be an apathetic lowland.

mountain would have two aspects: an Apollonian aspect consistent in the clarity of summits and the crystal of figures, and a Dionysian aspect which becomes confused with the deep, intoxicating, primitive dance, which was that of the earth millions of years ago, in which the memory and continuance remain. Even frozen, stopped, they continue moving, dancing, the mountains dance, at least the Alps dance, and the Caucasus, Elbourz, Hindu Kush without a doubt also, although in reality I did not see them dancing. The monumental Ecrins dance; the beautiful spirals of the massive Belledonne, Oisans or Trièves also dance, in Isère. Maybe even by dancing they imprint a general rhythm in the terrestrial surface, which without them would be an apathetic lowland. waiting, before taking back its course. So, because of its physical and calligraphic aspect, the writing in itself becomes poetry.

waiting, before taking back its course. So, because of its physical and calligraphic aspect, the writing in itself becomes poetry. jagged, carnal, and pagan, it says and hides Italy. To the west is Vercors, the poor mountain glides in parallel to the flow of the Rhone, but opposite this flow. The Vercors goes back up towards the north. The plateau of Vercors hides the Rhone and goes the wrong way from this river where it takes form and increases the power of the South. The Vercors says and hides the South.

jagged, carnal, and pagan, it says and hides Italy. To the west is Vercors, the poor mountain glides in parallel to the flow of the Rhone, but opposite this flow. The Vercors goes back up towards the north. The plateau of Vercors hides the Rhone and goes the wrong way from this river where it takes form and increases the power of the South. The Vercors says and hides the South. not the Tibetan axial mountain, which is not itself the mountain-volcano of the Indonesian archipelago, or because the Apennines act as the spinal column in a country, while the Caucase separates the world from the steppes of the Middle East. Their action, their function is not the same. And their name also, consequently. From country to country, from continent to continent, mountains do not make the same thing. Until the north.

not the Tibetan axial mountain, which is not itself the mountain-volcano of the Indonesian archipelago, or because the Apennines act as the spinal column in a country, while the Caucase separates the world from the steppes of the Middle East. Their action, their function is not the same. And their name also, consequently. From country to country, from continent to continent, mountains do not make the same thing. Until the north.